.png)

A.Garrett

I’m

not

certain

how

it

happened,

but

it

did.

I

was

in

the

throes

of

writing

The

Killing

Game

when,

one

day,

I

looked

at

a

photograph

and

met

the

gaze

of

a

man

from

the

former

Yugoslavia.

In

my

head,

I

heard

a

voice:

“Write

a

story

about

my

country.”

The

words

were

so

vivid,

as

if

the

speaker

was

right

there

with

me.

Whose

voice

was

it?

God’s?

…

Someone else’s?

It

was

impossible

to

ignore,

and

I

couldn’t

let

go

of

the

idea.

I

tried

to

set

it

aside,

but

within

fifteen

minutes,

I

found

myself

typing

the

opening

sequence

on

my

computer.

By

then,

the

story

had

unfolded

fully

in

my

mind,

eager

to

be

told.

This

happened

during

the

Christmas

holiday

of

1994,

while

the

siege

of

Sarajevo

raged.

I

had

followed

news

of

the

war, yet I couldn’t fully grasp it.

The

media

framed

the

conflict

as

“ethnic

cleansing

due

to

religious

differences,”

but

that

felt

like

a

shallow

explanation.

So

I

started

digging.

I

began

asking

questions,

discovering

that

much

of

the

truth

was

buried

beneath

layers

of

wartime

propa

-

ganda.

I

sought

out

people

from

the

former

Yugoslavia

and

found

them.

They

shared

varied

perspectives,

and

the

complexity

of

their insights was overwhelming.

What

I

gathered

left

me

with

more

questions

than

answers.

But

that

confusion

became

the

heart

of

my

story.

Misconceptions,

lies,

deceptions,

loss,

and

lost

causes

would

shape

the

narrative

about

a

place

I

had

never

studied

or

visited.

I

had

seen

much

in

life,

but

not

war—so

how

would

I

write

about

it?

First,

I

had

to

decide

on

the

story’s

focus.

That

choice

came

in

an

instant:

interpersonal

relationships.

But

what

kind?

Naturally,

a

man

and

a

woman,

though

not

a

typical

re

-

lationship.

War

complicates

things,

doesn’t

it?

Were

they

both

from

Yugoslavia

or

from

elsewhere?

If

both

from

Yugoslavia,

perhaps

they’d

be

desperate

to

escape;

if

from

differ

-

ent

nations,

what

would

bring

them

there,

and why?

At

the

time,

several

movies

were

already

ex

-

ploring

this

conflict,

but

my

story

needed

a

unique

angle.

I

wanted

to

tell

the

untold,

ev

-

eryday

stories

of

those

fighting

simply

to

survive.

I

wanted

to

highlight

the

quiet

he

-

roes

who

struggled

to

help

others

amid

the

chaos.

The

news

often

depicted

civilians

as

frenzied,

scrambling

for

survival—if

they

mentioned

them

at

all

beyond

major

atroci

-

ties.

But

the

press

thrives

on

sensationalism.

I

wanted

something

deeper,

something

that

spoke to the heart and soul of the people.

The

answer

became

clear:

a

man

from

Yugoslavia

and

a

woman

from

America.

But

what

would

compel

her

to

leave

her

comfort

-

able

life

in

the

U.S.

for

a

war-torn

country?

The

answer

lay

in

a

concern

that

had

haunted

me

since

I

first

heard

of

the

war—the

children

who

had

lost

their

parents.

An

orphan

could

be

the

catalyst,

a

motiva

-

tion

strong

enough

to

pull

her

from

her

safe

environment.

So,

the

story

would

revolve

around

a

man

from

Yugoslavia,

a

woman

from America, and an orphan.

I

wrote

a

rough

sketch

before

I

discovered

the

documentation

of

the

war’s

atrocities.

My

sketches

are

cohesive

outlines

of

events

as

they

will

unfold,

usually

requiring

more

de

-

tailed

work

later.

I

drafted

this

sketch

before

reading

about

the

prison

camps

held

by

all

three

warring

sides—Muslims,

Croatians,

and

Serbians.

By

these

ethnic

labels,

I

mean

the

military

factions

involved,

not

the

civil

-

ians;

however,

nationalist

ideologies

often

spilled

into

civilian

life

as

well.

My

story,

however,

focuses

on

one

man,

driven

solely

by

a

sense

of

what

is

right

according

to

God’s laws.

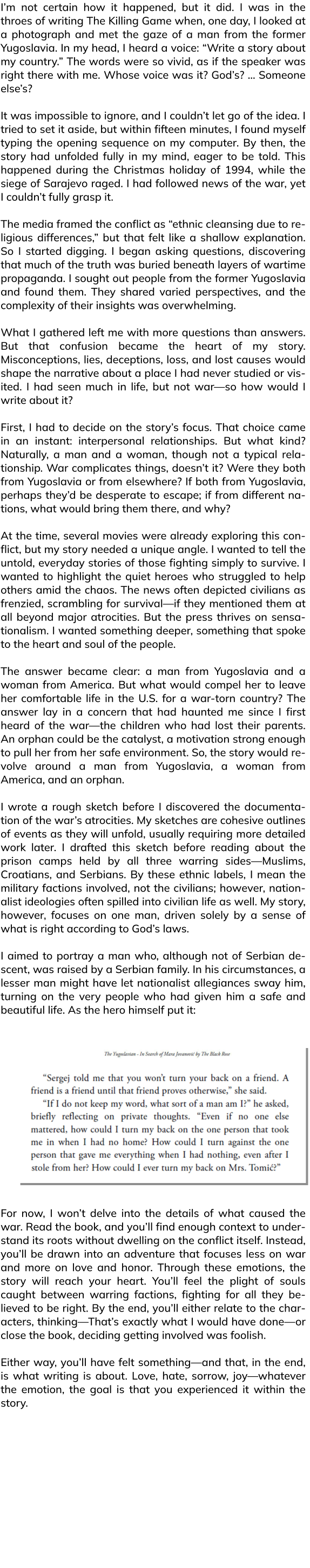

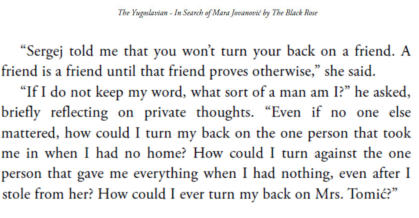

I

aimed

to

portray

a

man

who,

although

not

of

Serbian

descent,

was

raised

by

a

Serbian

family.

In

his

circumstances,

a

lesser

man

might

have

let

nationalist

allegiances

sway

him,

turning

on

the

very

people

who

had

given

him

a

safe

and

beautiful

life.

As

the

hero himself put it:

For

now,

I

won’t

delve

into

the

details

of

what

caused

the

war.

Read

the

book,

and

you’ll

find

enough

context

to

understand

its

roots

without

dwelling

on

the

conflict

itself.

Instead,

you’ll

be

drawn

into

an

adventure

that

focuses

less

on

war

and

more

on

love

and

honor.

Through

these

emotions,

the

story

will

reach

your

heart.

You’ll

feel

the

plight

of

souls

caught

between

warring

fac

-

tions,

fighting

for

all

they

believed

to

be

right.

By

the

end,

you’ll

either

relate

to

the

charac

-

ters,

thinking—That’s

exactly

what

I

would

have

done—or

close

the

book,

deciding

get

-

ting involved was foolish.

Either

way,

you’ll

have

felt

something—and

that,

in

the

end,

is

what

writing

is

about.

Love,

hate,

sorrow,

joy—whatever

the

emo

-

tion,

the

goal

is

that

you

experienced

it

within the story.

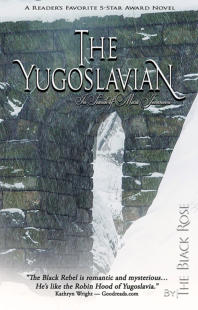

Writing The Yugoslavian

When the Story Chooses You

- PREVIEWS

- The Killing Game

- The Chase

- The Final Hour

- Time - A Precious Commodity

- The Lost Days - Ives' Sorrow

- The Last Hope - Shattered Hearts

- Unrequited

- The Lesser Evil - Let the Games Begin

- The First Move Teaser

- The First Move - Ink

- The Yugoslavian - A Wanted Man

- The Yugoslavian - Tess' Travel Journal

- Cold - The Black Rebel

- VISUAL ESSAYS

- SOUNDTRACKS

- PODCASTS

"For the Word of the Cross is folly to

those who are perishing, but to us who

are being Saved it is the Power of God."

1 Corinthians 1:18

-1.png)

- Home

- Begin

- The Stories

- Narratives

- Narratives

- Previews

- Previews

- The Killing Game

- The Chase

- Time - A Precious Comodity

- The Final Hour

- Ives' Sorrow - The Lost Days

- Shattered Hearts - The Last Hope

- Unrequited - Eichel & Allina

- Let the Games Begin - The Lesser Evil

- The First Move Teaser

- The First Move Ink

- A Wanted Man

- Tess' Travel Journal

- Cold - The Black Rebel

- Visuall Essays

- Soundtracks

- Podcasts

- Behind the Scenes

"For the Word of the Cross is folly

to those who are perishing,

but to us who are being Saved

it is the Power of God."

1 Corinthians 1:18