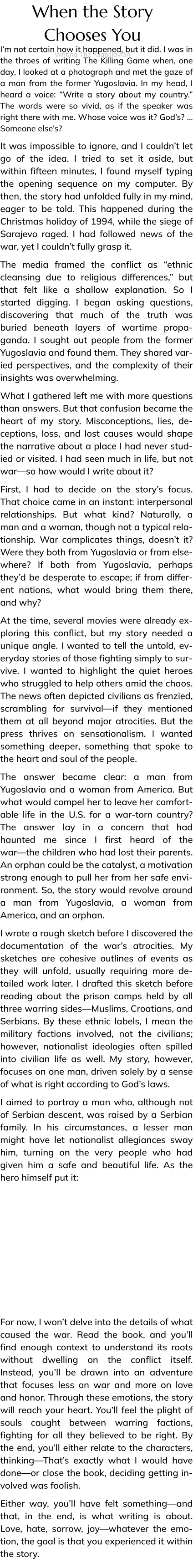

"For the Word of the Cross is folly to

those who are perishing, but to us who

are being Saved it is the Power of God."

1 Corinthians 1:18

- Home

- Prologue

- The Stories

- Narratives

- Previews

- The Killing Game Series

- The Killingi Game

- A Shark in Murky Waters

- The Chase

- Time - A Precious Comodity

- The Final Hour

- When Power isn't Enough

- Ives' Sorrow - The Lost Days

- Shattered Hearts - The Last Hope

- Unrequited - Eichel & Allina

- The Heroine behind the Hero

- Let the Games Begin - The Lesser Evil

- The First Move Teaser

- The First Move Ink

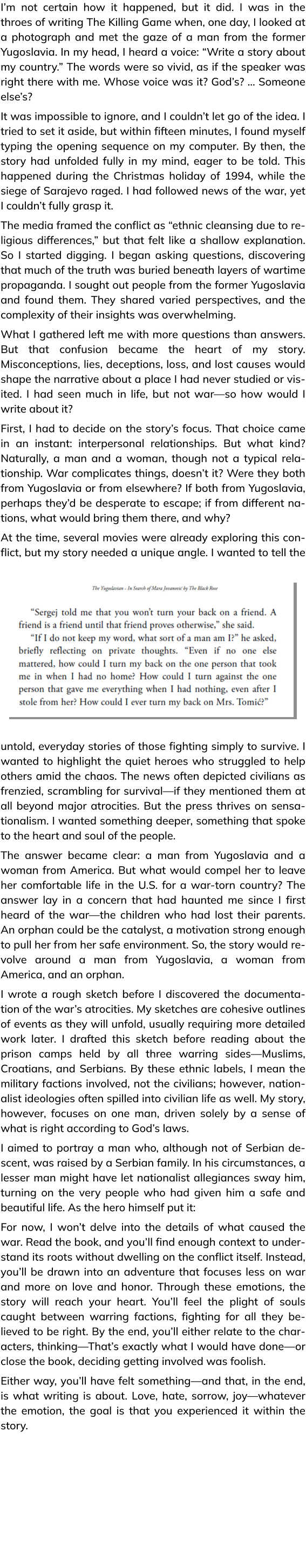

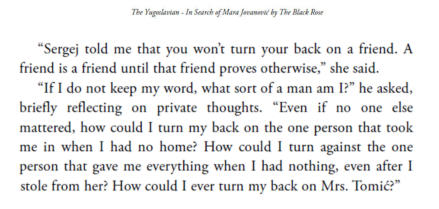

- The Yugoslavian Series

- Why Backstory Matters

- The Killing Game Series

- Visual Essays

- Soundtracks

- Podcasts

- Previews

- Behind the Scenes (Privé)

"For the Word of the Cross is folly to

those who are perishing, but to us who

are being Saved it is the Power of

God."

1 Corinthians 1:18